The following reading about Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 is taken from a 2015 study guide created by Facing History and Ourselves. Any additions that refer to current events or edits for clarity are clearly marked between [brackets]. All hyperlinks have been added by Jobsite.

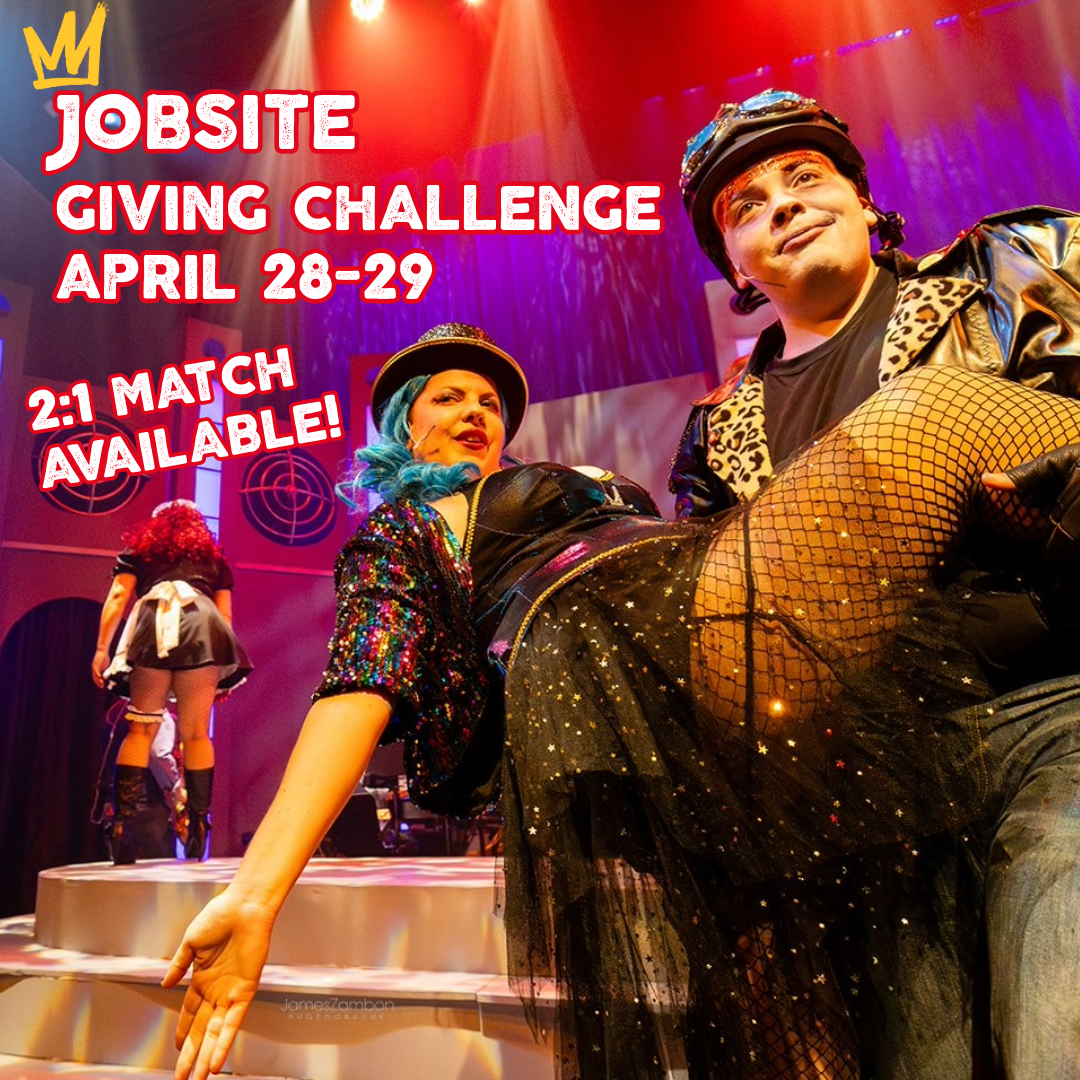

Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 plays the reconfigured-for-distance Jaeb Theater Nov. 11 – Dec. 2 on Tue. and Wed. evenings at 7:30pm.

Riots, Then and Now

The “Los Angeles riots” of 1965 and 1992 began with the arrest of an African American. Distrust between the police and blacks has been a part of life in Los Angeles—and the nation—for generations. In a 1992 interview with Anna Deavere Smith, Stanley K. Sheinbaum, the former president of the Los Angeles Police Commission, recalled meeting with young gang members just a week or two before the violence in Los Angeles erupted. The group was trying to work out a gang truce, when Sheinbaum arrived with Congresswoman Maxine Waters. Two days later, he received a letter from an officer saying “You went in and talked to our enemy.” He responded by explaining that this was an opportunity to speak with and learn about “these curious people about whom I knew nothing.” At the end of his speech, the officers asked, “So which side are you on?” He responded with his own question: “Why do I have to be on a side? There’s a problem here.”

[“Los Angeles, in many ways, is America’s reference point for urban racial unrest” Many have noted links from the 1965 and 1992 uprisings to the unrest in LA during 2020]

In 1992, the Oregonian reported that “complaints of police brutality and racism” and “verdicts and settlements against the [Los Angeles Police] have risen over the decades, from $553,000 in 1972 to $6.4 million in 1989 to $8 million in 1990.” The article went on to note that “in the first two months of this year there was a sharp rise in complaints filed against the police—127 for two months, against a yearly average over the last five years of about 600. About 25 percent of the complaints involve allegations of assaults by the police. On average, only two of the 600 complaints a year result in felony charges.”

[LA County Sherrff’s Dept. spent over $81 million in litigation expenses during FY 2018-19, up from $62 million in the previous FY.]

[In 2001], Bob Herbert, a columnist for The New York Times, wrote:

I can still remember leafing through Life magazine in July 1967. I was just back from overseas, a 22-year-old sergeant stationed at Fort Belvoir, VA, where I would serve out my last few months in the Army.

On the cover of the magazine was a photograph of a 12-year-old boy lying unconscious on the filthy pavement of a street in Newark, NJ. He was bleeding from gunshot wounds.

The story was about the riots that in a few days had all but ruined Newark. I froze when I got to page 16. There was a photo of a guy I knew from Montclair, Billy Furr, caught in the act of looting beer from a liquor store. The photo was the first in a frightening series that showed cops suddenly appearing at the scene, Billy Furr running, a cop in a helmet aiming a shotgun at Billy’s back, and Billy continuing to run.

The cop shot and killed him. On page 22 was a picture of Billy lying on the sidewalk, dead at 24. The cop with the shotgun stood over the body. He didn’t look particularly concerned. Pellets from the shotgun blast also struck the 12-year-old boy whose photo was on the magazine’s cover. Though seriously wounded, he would survive. The cop didn’t seem too concerned about him either.

I remember sitting in the barracks at Fort Belvoir, stunned. And I still feel strange whenever I see those pictures.

Last week there were riots in Cincinnati, sparked by the fatal shooting of 19-year-old Timothy Thomas, a black kid who was said to have run from a cop. Mr. Thomas was wanted for failing to respond to several misdemeanor traffic charges. Five of the charges were for not wearing a seat belt while driving.

As in Newark, the rioting in Cincinnati was an explosive expression of the rage among blacks that had built up at the hands of the police, public officials and other influential figures throughout society, most of them white. You’ll find that kind of maddening, simmering rage everywhere you find black people in the United States. It is the rage that comes from living in a society where every day there are humiliating reminders of one’s debased status.

But race issues are complex and sometimes paradoxical. It is possible to look back over the past half-century and conclude that we have come a long way and made surprisingly little progress, all at the same time.

Police brutality, a criminal justice system that works one way for whites and another for blacks, employment discrimination, housing discrimination, the continuing fanatical resistance to real integration, social ostracism— these are not remnants from some distant past, but rather the everyday reality of life for blacks in America in 2001.

Black people are angry because there is more than ample reason to be angry.

That said, there is something both weird and very wrong about continuing to respond to the outrages of racism and police brutality by throwing bottles, smashing windows, overturning cars, looting stores, burning down buildings, shooting at police officers and dragging innocent white motorists from their vehicles and attempting to beat and stomp them to death.

I felt as sick watching the video of Reginald Denny being hauled from his truck and savagely beaten during the Los Angeles riots in 1992 as I did looking at the sequence of photos of Billy Furr being killed in 1967.

Few blacks ever riot. And some of the worst rioting over the past four decades has had surprisingly interracial components. There was widespread looting by whites as well as blacks in the horrible rioting that brought Detroit to its knees less than two weeks after the outburst in Newark. And more than half of the people arrested during the 1992 rioting in Los Angeles were Hispanic.

But after the riots, when the smoke from the arson fires has lifted and the spasms of violence have passed, it is the black residents who, inevitably, have endured the worst of the suffering—lives lost, neighborhoods destroyed, hopes for the future derailed. (1)

For Consideration:

What does Sheinbaum’s experience suggest about the divisions between the police and African Americans in the city? How might they contribute to myths, misunderstandings, and misinformation? How might they fuel violence?

✦ ✦ ✦

What are the alternatives to riots? What part can education play? The media? [The arts?] What can individuals do to make a difference? What is the role of law? How do laws get changed? What would a “smarter, more effective response” to racism and police brutality be?

✦ ✦ ✦

Read the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It guarantees the right of individuals to associate, advocate, and even express outrage. How have individuals and groups in Los Angeles and other cities used these protections to bring about change, including changes in laws? [How does Gov. DeSantis’ proposed bill possibly infringe on first amendment rights, or how might such a bill be abused by law enforcement and local governments?]

✦ ✦ ✦

In a 1992 interview with Anna Deavere Smith, artist Rudy Salas recalled being harassed by the police in the 1940s because he was a “zootsuiter.” “How do you think a father feels,” he asks, “stuff that happened to me fifty years ago happened to my son?” Why does history repeat itself? What can be done to break the cycle?

✦ ✦ ✦

[Consider what you know or have learned about the uprisings listed above in 1965, 1967, 1992, and 2001 — or any American instance of mass racial violence — and the uptick in peaceful demonstrations that have sometimes led to disconnected violence in the wake of the murders of Black Americans like Ahmaud Aebery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Elijah McCain. We again offer the same questions: Why does history continue to repeat itself? What can be done to break the cycle?]